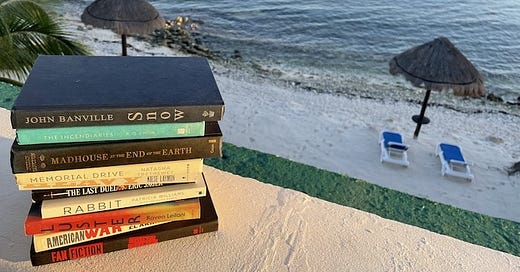

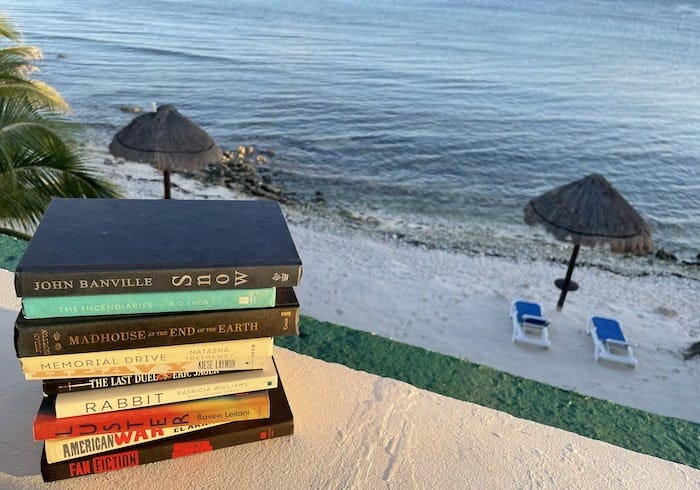

Akumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico is a very special place for my husband and me. We try to steal away for a week every few years and do nothing but sit on this beach and read books.

When it gets too hot, we walk out into Half Moon Bay and snorkel with turtles, rays, octopuses, and all the multicolored fish that live on the reef.

Every year, my stack of books spans genres, years, and sizes, and I always bring extras to suit my mood. This year, our first since the pandemic, I gravitated to powerful Black stories, both fictional and nonfictional, and I am surprised to have read no scifi at all.

There are so many incredible moments and people across these books that I hope you get a chance to read.

If nothing else, don’t miss American War and Rabbit, easily the best two books I have read all year.

Some quick reviews, in the order in which I read them:

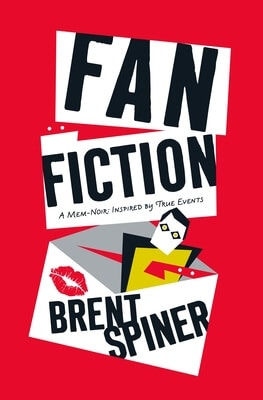

Fan Fiction, by Brent Spiner

Cute. Light. Inoffensive. I read it on the plane ride to Mexico.

Is it clever? A little. The lingering impression is that Spiner had a lot of fun writing this, and a lot of latitude in publishing it because of his celebrity.

Rabbit, by Patricia Williams

A few days before reading Rabbit, my husband and I were talking about how it is a necessary yet impossible task to identify every space in life where American society privileges (or, using Kiese Layton’s words in Heavy, [em]powers) white over Black lives.

It is also a profound and necessary challenge to explain such systemic racism to people who don’t see it.

For me, Ms. Pat’s book lays out that exact argument in fearless, funny, and real language. Her story is incredible in its own right, as she grows from the unlikeliest of circumstances to become a hilarious and fearless comedienne.

It is also peppered with references to the ways in which distant politicians and supposedly well-meaning folks enacted policies that looked like “help,” but were ultimately background noise to her real life. She unflinchingly takes us into her uproarious and tragic childhood and unapologetically shows how she made choices with the information she had in the moment.

Hers was not the theoretical life of tv shows and politics, but the real life of a real woman.

Funny, heartwarming, and searingly bold, this is a must-read memoir.

American War, by Omar El Akkad

El Akkad’s staggering work will haunt me for a very long time. A critically-acclaimed journalist, he has taken the realities of wartime, refugee camps, and the climate crisis and transformed them into a chilling and all-too-believable future. The result is powerful and terrifying and too-real, despite being set in a dystopic, climate-ravaged future.

His choice to intersperse the main narrative with “official” communications, histories, and news reports shines a stark light on the difference between politics and lived reality on the ground, as well on the fact that those in charge and those doing the living rarely care about each other. The addition of an external narrator to begin and end the book also adds to its impact.

By the end, El Akkad does not fail to rebuke any reader who has missed the truth of Sarat’s journey.

You must read this book!

Luster, by Raven Leilani

Luster was not at all what I expected. I would recommend it highly to anyone looking for a stunning and breathtaking character study.

Edie is a 23-year old Black woman fully aware of her own personal biases, challenges, and traumas, yet seemingly powerless to figure out a way to break down the walls she knows are holding her back.

Leilani’s writing is raw and bold and remarkable. Edie’s fearless truths and aches and pains make reading this feel like you are being let in on a dangerous and all-too-real secret.

It reads like a memoir, or an ode to lost youth, or something haunting in between.

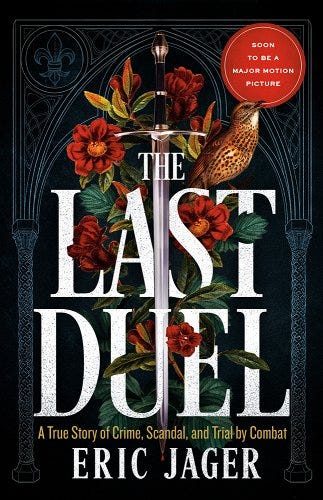

The Last Duel, by Eric Jager

I have no idea how the general public got through the first 3/4 of this book, thick with dull medieval facts, convoluted social dynamics, and intricate 14th c. formalities. But then I got to the duel and found myself breathless as Jager described the legendary event with cinematic grandeur.

It is a remarkable feat to make something like arcane medieval legal practices exciting. Understanding that history is a story, not just a static event in the past, is the hallmark of every good historian, and so few academics can pull it off.

Kudos to Jager.

Memorial Drive, by Natasha Trethewey

Natasha Trethewey won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry and this personal account (more like accounting) of recovering her memories of her mother is an extended, lyrical reflection on grief, trauma, and how it radically changes a life.

Her poetic voice is mesmerizing, although I found myself wondering how such a fluid, introspective, and powerful memoir would have been published if she didn’t already have a Pulitzer.

Hers is a brief, soulful expression of grief unresolved. The power is in her voice and her resistance to resolution. She reminds us that life is not always happy endings.

Heavy, by Kiese Layton

What an absolutely fantastic memoir!

Coincidentally, reading Heavy after Memorial Drive felt like I was reading the counterpoint to Trethewey’s tale. Layton’s story is an incredible tragedy that he gifts the reader with. Yes, it is a gift of a book, the sort of unselfish, impossible tale that all memoirists should aspire to write.

The ache of his writing this over decades, and of writing it directly to his mother bleeds through the pages. He carries on his literary and spiritual shoulders every possible meaning of the word “heavy” and the reader struggles under the weight of it all.

You’re left wondering how he has survived it because surely the rest of us would not have been as strong as him.

The Incendiaries, by R. O. Kwon

I feel like my take on The Incendiaries is like my take on Little Fires Everywhere: I just didn’t find it all that compelling.

Based on the critical acclaim, I am certainly in the wrong, but it’s also moments like this that remind me why all writers should write. Some people will love your work, and some won’t, but all that matters is that you put pen to paper (or fingers to keys) and let something extraordinary happen.

As for The Incendiaries, I found Kwon bouncing between 3 characters distracting since one character was written in first-person, one was written in a hypothetical first-person, and one in a strangely unreliable third-person. I just didn’t get the point of the multi-perspective device here.

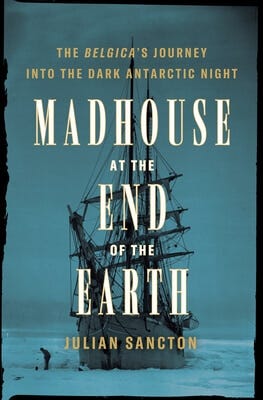

Madhouse at the End of the Earth, by Julian Sancton

There is a running joke in my house that if someone gets lost somewhere cold, I’m going to read the book about it. From Everest to the Antarctic to the Andes, I’m a sucker for the “everyone almost died in the cold (or actually did)” genre.

So trust me when I say that Sancton’s addition to the canon is a masterpiece! It reads like a novel, and I found myself wondering how I had never heard of the expedition of the Belgica before.

This is the perfect example of the story that you have to write when you discover all the evidence is there, but no one has gotten around to telling it yet.

Write your story!

And read this book!

Snow, by John Banville

Banville is one of Ireland’s greatest living writers. This is my first time reading him, and I’ll concede his gift of language is so precise and elegant that you can almost hear the rustle of curtains in dusty rooms or feel the chill of the snow outside.

For all his mastery of language, however, his command of surprising plot twists leaves much to be desired. At best, the plot was predictable and disappointing, at worst it felt dangerously bigoted.

Dare I say he could have used a book coach to help him with the plot, and a sensitivity reader as well.

n.b. All book links are affiliate links to bookshop.com. If you use these links to buy something, I may earn a small commission. I affiliate with bookshop.com in support of indie bookshops. Support your favorite local independent bookshop any time you can. Thanks.